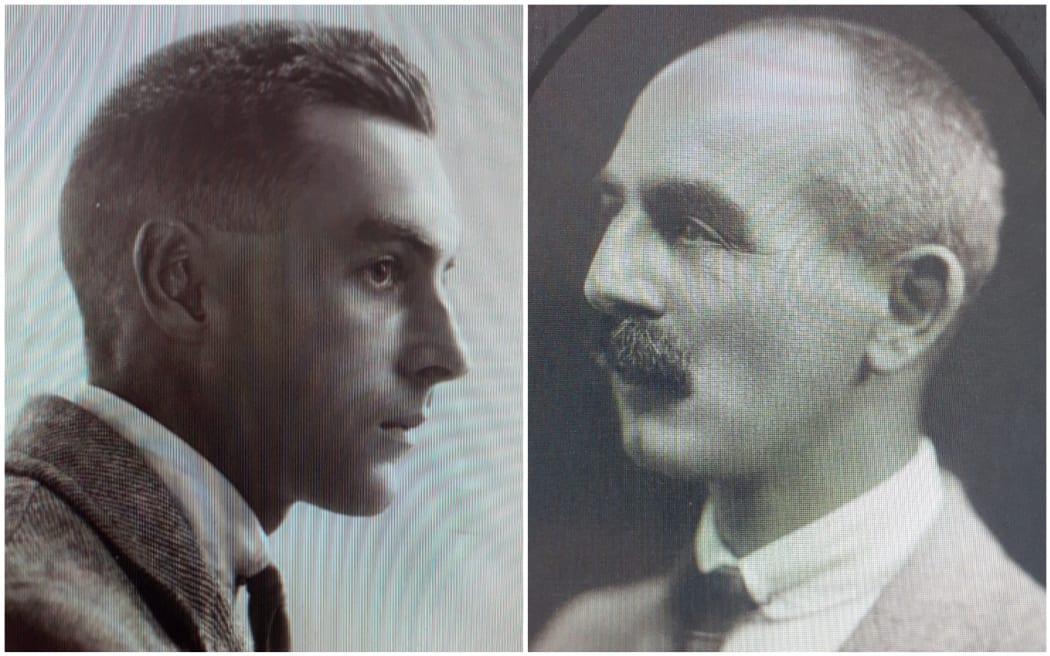

Returned soldier and poet Walter D’Arcy Cresswell (left) was shot by Whanganui mayor Charles Mackay in 1920. Photo: Supplied via LDR

Paul Diamond spent 18 years “searching for traces” of the circumstances surrounding the sensational 1920 shooting in Whanganui of returned soldier and poet Walter D’Arcy Cresswell by Whanganui mayor Charles Mackay.

The author is somewhat nervously awaiting the city’s reaction to the release this week of his new book, Downfall – The Destruction of Charles Mackay. The book hints the town did its utmost to cover up not only the scandal of homosexuality exposed by the shooting, but a darker secret that has yet to be uncovered.

- Listen to Kim Hill interview Paul Diamond on Saturday Morning.

Diamond (Ngāti Hauā, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi), curator Māori at the Alexander Turnbull Library, says he was advised by an historian not to try to solve the mystery of what happened, but to focus instead on the consequences for the brilliant Mackay, who was outed as a homosexual during the trial that followed.

“Whanganui’s got an amazing history and the book tells a bit of that history. It’s not just a story about these two men and their families, it’s actually about the town.

“It’s very interesting how little reference there is to this incident. It’s either completely ignored or it’s alluded to as ‘unfortunate circumstances’.

“That’s how they were writing about it in the 1960s. When Helen Shaw tried to research this for a book about D’Arcy Cresswell, she was told to either tone it down or leave it out altogether because it was unsavoury and because there were members of Mackay’s inlaws still living in Whanganui.”

Cresswell, 24, from Timaru, was visiting cousins in Whanganui when Mackay, 20 years his senior, shot the younger man in Mackay’s second-floor office in Ridgeway Street, now part of the city’s heritage precinct.

“The book centres around this incident that grabs peoples’ attention now just like it must have in May 1920 when people who happened to be in Ridgeway Street saw a chair crashing through the window and a gun being fired and apparently someone standing at the window and calling for help,” Diamond says.

“All we’ve got to go on as to what happened, apart from those eye-witness accounts of what people saw that Saturday afternoon, is this typewritten statement that D’Arcy Cresswell gave police from hospital. A really odd statement, not signed by him, but weirdly it was signed by Mackay, who said ‘as far as it relates to my own acts and deeds, I admit this statement to be substantially true’.”

Cresswell’s statement reveals he was blackmailing Mackay.

After apparently discovering Mackay was gay, he was threatening to reveal Mackay’s homosexuality if the older man did not resign as mayor.

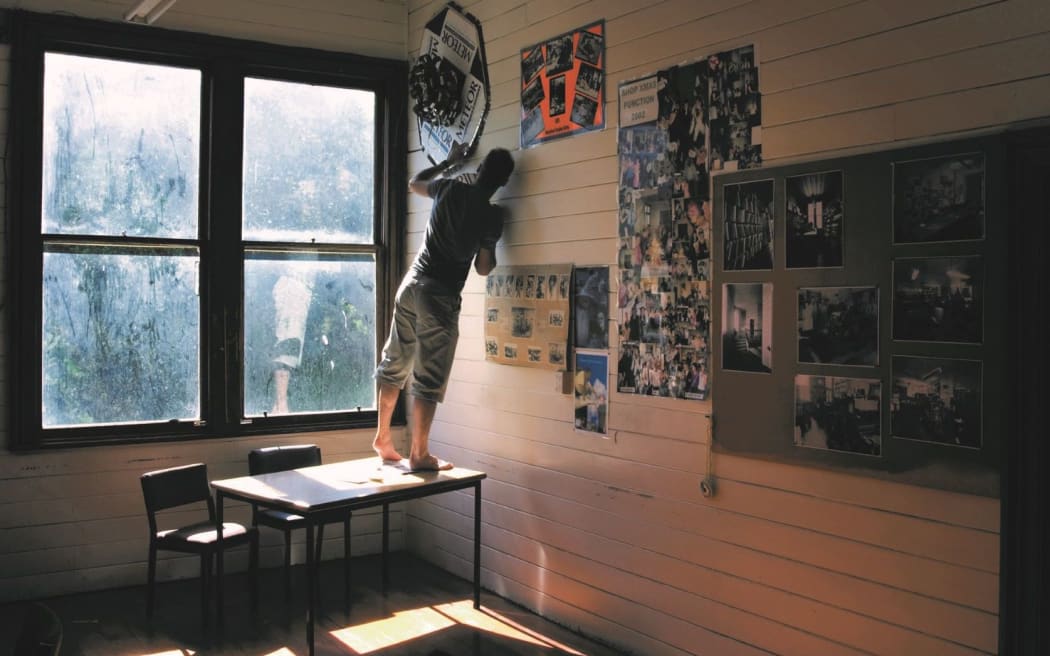

This photo taken from Downfall – The Destruction of Charles Mackay shows Paul Diamond looking for bullet holes in Mackay’s office. Photo: Supplied via LDR

Just over a century later, Diamond believes there is more to the story.

“After thinking about this, and putting it together with other things, I strongly suspect there was more going on in Whanganui than we might realise and I think [Cresswell’s statement] was to shut things down,” Diamond says.

According to one paper, the court was planning to hear evidence from Cresswell at the hospital, where he was still recovering from the gunshot. But Mackay endorsed Cresswell’s statement and pleaded guilty to attempted murder, revealing during the trial he had been seeking treatment from a hypnotherapist for the “nervous disorder” of homosexuality.

“It was a big scandal. But you’ve got another layer of strangeness in this story: one gay man blackmailing another, and the town trying to shut this thing down as quickly as they could.”

The town’s reaction was so severe that Diamond suspects there may be a deeper secret: a hidden history yet to be discovered because Whanganui society was so successful in covering up the incident.

“Some people have assumed that there was some sort of relationship between the two men because Cresswell was gay as well, although he didn’t say that at the time. I don’t think there was something between the two men – I think that Cresswell had discovered something perhaps involving people other than Mackay, perhaps that something else was going on in the town, perhaps that other men were involved.”

Diamond says veiled references in newspapers of the time speak to something else going on.

“I talk about this in the book. It’s circumstantial evidence, it’s very sketchy, but there’s something that people kept referring to about others being involved. That then would make sense of why the whole town would try to put a lid on this thing.

“A lot of energy went into expunging Mackay from Whanganui’s history.”

The book on Charles Mackay is released on 10 November. Photo: Supplied/ Massey University Press

Mackay was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 15 years’ hard labour.

Despite serving some 12 years as Whanganui mayor, his portrait was removed from the walls of the council offices, his name was ground off the foundation stone of the Sarjeant Gallery, and Mackay Street in Whanganui East, named after him, was changed to Jellicoe Street. His wife, socialite Isobel Duncan, divorced Mackay, reverted to her maiden name, changed the names of their three daughters to Duncan and severed all contact with Mackay.

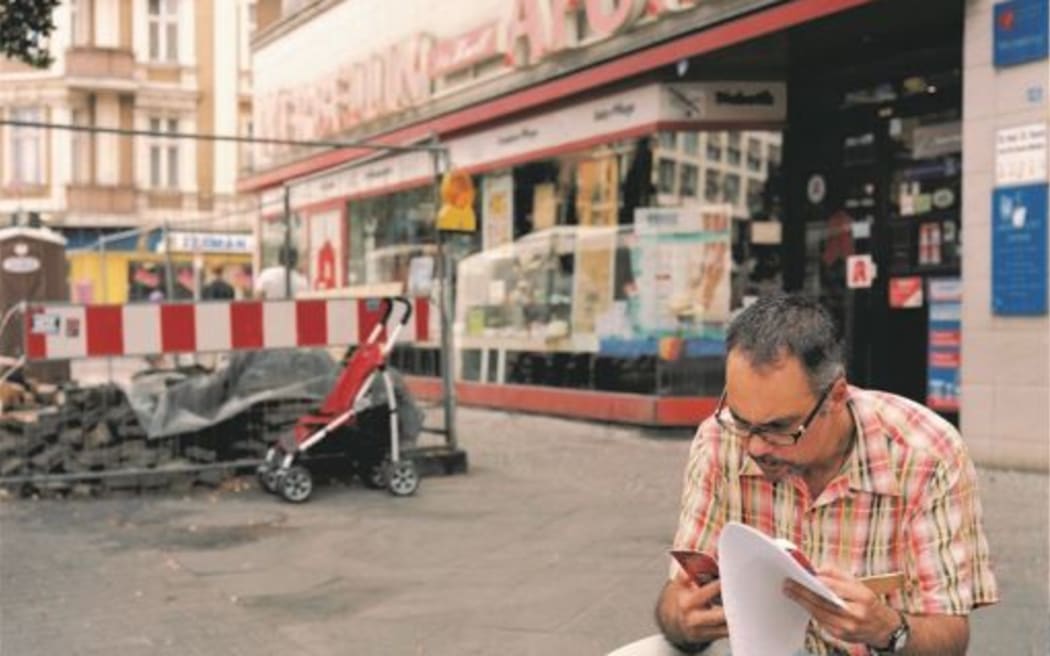

Mackay was released after six years on the condition he leave the country. He headed for London, where he worked in advertising, and then Berlin, where he taught English and freelanced as a journalist, having articles on Weimar Berlin published in Australia and New Zealand under a nom-de-plume, including in Manawatū and Whanganui.

“He was right at the heart of that Weimar world of balls and parties,” Diamond says.

Mackay’s new life was short-lived. In 1929, he became the final victim of the German capital’s May Day riots, fatally shot by a police sniper while trying to cover the story.

Diamond describes Mackay’s story as strange and tragic.

“What happened in that office set in motion these events. It did kind of destroy his life. It was a tragedy for both the families these men came from.

“But it’s also a story of resilience. Mackay kept picking himself up and carrying on. He seemed to have this incredible resilience. But he did end up on that street corner in Berlin and it was completely the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Diamond says it has been interesting to see how the villain and victim of the story have shifted over time.

“In 1920, it was very clear in the papers: the young man was the hero and this older man was the villain. Now, people look at it differently. Even though Mackay shot someone, he’s very much seen as a person who was victimised because of his homosexuality.

“Even if we don’t know exactly what it meant to be a homosexual then, I think we do know that the way these men were treated and the way they lived their lives was influenced by what other people thought their homosexuality meant.

“Even though Mackay was in prison for attempted murder, there are loads of references in newspapers and archives to him being a pervert. That is interesting language and it shows that he was seen as a gay man – that’s why I believe he was sent to New Plymouth prison, which was at that time set aside for sex offenders, which included homosexuals.”

Another picture from the book which shows Paul Diamond “searching for traces” of Mackay near where he was fatally shot in Berlin. Photo: Supplied via LDR

Diamond says he hopes the new book will lead to more information coming to light in and beyond Whanganui.

“I still think there must be connections with these stories in other parts of the country. D’Arcy Cresswell’s family, for example, left Whanganui and ended up in Auckland.

“It is a hundred years ago, but I do wonder if more will emerge now that we’ve finally got a book on this. There have been newspaper articles, plays and books that have referenced the shooting but until now no-one’s written a book.

“It’s a collection of traces that I’ve tried to make sense of. We are talking about a time when [homosexuality] is illegal, when you can’t talk about things, so it’s very hard to get a sense of what went on, let alone what people thought.

“I really do wonder if there are other traces out there.”

Diamond says when he started researching the book in 2004, there was no-one alive who would have been an adult at that time and he was forced to rely on other sources.

“The gaps and the absences are quite telling. I think that’s a shame and maybe that’s a difference in our time in history now: we are a little bit more comfortable about giving the full range of history and acknowledging that there were things that were happening like abortion and divorce and gay people. It’s all part of our history.

“I think Whanganui could do with a decent history because I ended up having to look in other places. There are some quite good theses about Whanganui, but to be honest the published histories are so superficial they sell the town short … and of course there’s the whole disconnect with Māori history.”

Diamond says it’s clear that is changing in the river city.

“With all the things that are going on with Treaty settlements, and the changing of the town’s relationship with the river, the town is no longer turning its back and is more engaged in history in all sorts of ways.”

Downfall – The destruction of Charles Mackay is released on 10 November. Paul Diamond will give a public talk on Charles Mackay at the Davis Lecture Theatre on 19 November, and will lead historical walking tours in Whanganui on 18 and 20 November.